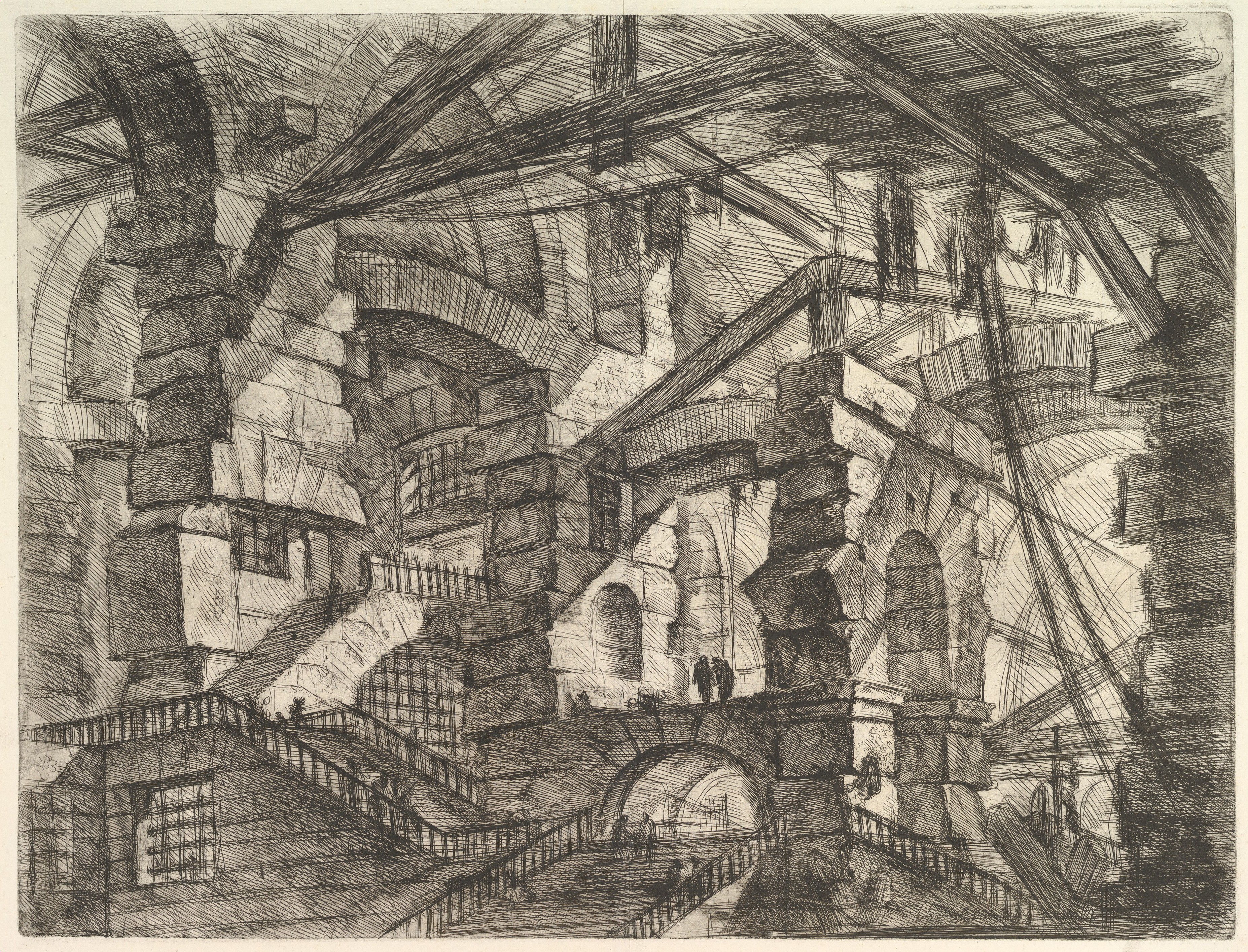

which record the scenery of his own visions during the delirium of a fever: some of them (I describe only from memory of Mr. Coleridge, who was standing by, described to me a set of plates by that artist. Many years ago, when I was looking over Piranesi's Antiquities of Rome, Mr. Thomas De Quincey in Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (1820) wrote the following: VENE’’ĢND: AD TERROREM INCRESCEN AUDACIAE IMPIETATI ET MALIS ARTIBUS INFAMES CEIUS RUNFELICIS SUSPE Though untitled, their conventional titles are as follows:ġst: ‘’INVENZIONE CAPRIC DI CARCERI ALL ACQUA FORTE DATTE IN LUCE DA GOVANI BOUCHARD IN ROMA MERCANTE AL CORSOĢnd ’’CARCERI D’INVENZIONE DI G. Numbers I to IX were all done in portrait format (vertical), while X to XVI were landscape format (horizontal+). Numbers II and V were new etchings to the series. For the second publishing in 1761, all the etchings were reworked and numbered I–XVI (1–16). Piranesi reworked the drawings a decade later. The first state prints were published in 1750 and consisted of 14 etchings, untitled and unnumbered, with a sketch-like look. They are capricci, whimsical aggregates of monumental architecture and ruin. While the Vedutisti (or "view makers"), such as Canaletto and Bellotto, more often reveled in the beauty of the sunlit place, in Piranesi this vision takes on what from a modern perspective could be called a Kafkaesque distortion, seemingly erecting fantastic labyrinthine structures, epic in volume. The images influenced Romanticism and Surrealism.

They depict enormous subterranean vaults with stairs and mighty machines.

PIRANESI PRISON SERIES

The Prisons ( Carceri d'invenzione or Imaginary Prisons) is a series of 16 prints by the Italian artist Giovanni Battista Piranesi in the 18th century. Read Piranesi, you will be rewarded for entering The World.Series of prints by Giovanni Battista Piranesi I would have also like to understand more of the motivation behind some people’s actions, but perhaps that will be for a sequel. Keeping track of that wasn’t too difficult. There aren’t many characters to juggle here, however, at times character’s names change. I won’t do you the disservice of revealing any sort of plot details because the joy of seeing and feeling it all unfold is why you come to read this book in the first place. This short, very accessible book should do well.Īnd it does take a bit to get going (surprising for such a short book), but once things are set into motion, the intricacies of all characters coalesce into a fulfilling climax. Piranesi feels like a “Hey, look fiction can be awesome!” advertisement. Now, I’m not a big fiction reader, but for those that knock fiction, why? Fiction is every bit as powerful as non-fiction, and in some cases can be more incredible than its fact-based counterpart. In the book, you’ll see all of Piranesi’s names used in some form and I’m sure that’s no accident. His work is almost immediately intricate as it is somehow familiar when you see it. Piranesi is perhaps inspired by Giovanni Battista Piranesi, an artist who created labyrinthian worlds in etchings. Not purposely, but I devoted an entire afternoon to soak up the constructed world that is “The House.” It is hard to imagine for me that a book of mere 272 pages could be so interesting and layered. As it all unravelled in front of me, I descended deeper. I felt as if I was the rather innocent Piranesi himself, picking up clues yet not knowing exactly the grander significance. Every so often a book comes along that, once I start reading it, I’m so deeply enthralled that I absolutely must finish.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)